What are peptides?

Our offer is consistently geared towards the scientific context.

We attach great importance to traceable quality, transparent analysis and a clear purpose as research reagents.

- made up of amino acids

- linked by peptide bonds

- Sequence determines properties

- Length mostly 2-50 amino acids

- Solubility depends on the structure

- Synthetic or biologically formed

- good dosage in vitro

- Common reagents in assays

The term peptide primarily describes the chain length: very short representatives are called dipeptides or tripeptides, longer ones often oligopeptides. Above a certain size, they are often referred to as proteins, although the limit varies depending on the field. The specific amino acid sequence is always decisive.

In everyday life, peptides are often confused with food supplements or medicine. In chemical terms, they are defined molecules that can be present in various forms, for example as a lyophilized powder for laboratory purposes. For practical work, it is important that identity and purity are documented in a traceable manner and that storage and handling are appropriate for stability. Anyone evaluating peptides should therefore always consider the sequence, purity, salt form and test documents together to ensure truly reliable results.

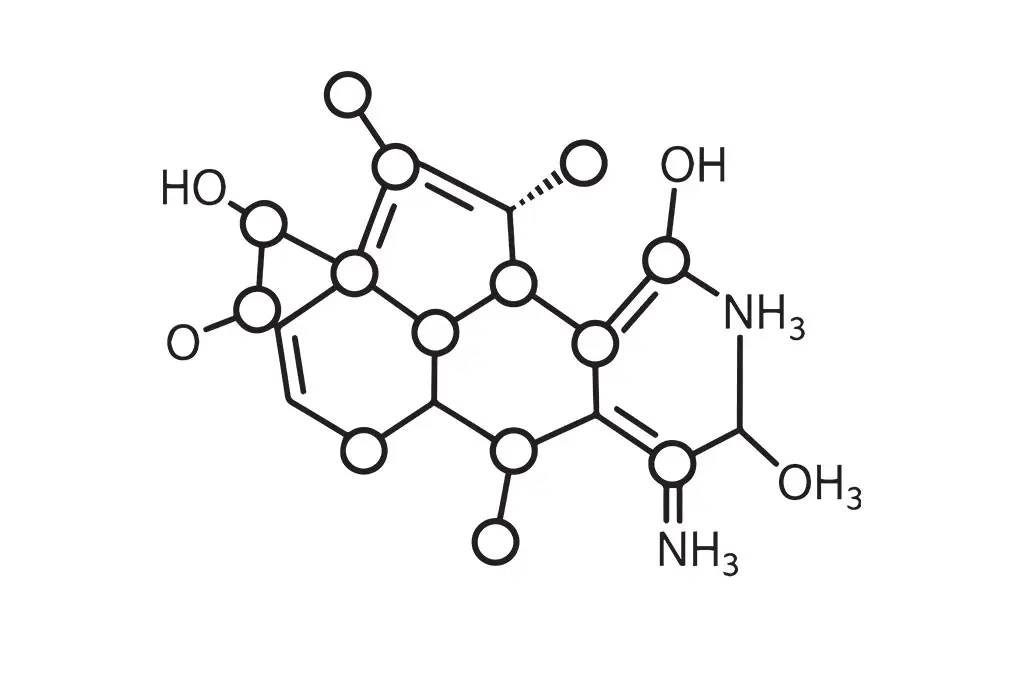

Structure of peptides: Amino acids, peptide binding, sequence

Peptides consist of amino acids in a fixed sequence. This sequence is the central blueprint: It influences charge, solubility, stability and binding behavior. Amino acids are linked via the peptide bond, which connects amino and carboxyl groups. For laboratory work, it is also important to know which end groups are present and whether a peptide carries modifications, as even small chemical details can often significantly shift measurement results.

- Building blocks: Side chains can be polar, non-polar, acidic or basic. This determines whether a peptide is more hydrophilic or hydrophobic and how it behaves in aqueous systems.

- Peptide bond: Chemically, it is relatively stable, but can be cleaved under unfavorable conditions. pH, solvent and enzymes determine how quickly degradation processes occur.

- Direction: Peptides have a clear orientation from the N-terminus to the C-terminus. Many interactions depend on where certain amino acids are positioned within the sequence.

- Sequence effect: An exchange of individual amino acids can change the spatial arrangement. This influences affinity and selectivity, even if the overall structure appears similar at first glance.

- Modifications: End caps, markers or non-natural building blocks can increase stability and detectability. For valid interpretation, such modifications must be consistently applied.

- Salt form: Many peptides are present as salt. Counterions and residual substances can influence solubility and assay behavior and are therefore part of the quality assessment.

In practice, it is not just "which peptide" that counts, but in what form it is present. Evaluating sequence, end groups and documentation together reduces misinterpretations and increases comparability between experiments.

Peptides, proteins, amino acids: clear differentiation

- Amino acids are individual building blocks with an amino and a carboxyl group.

- Each amino acid has a side chain that determines its polarity, charge and reactivity.

- In chains, neighbors and surroundings shift charges and bonding tendencies.

- A peptide is a chain of several amino acids linked by peptide bonds.

- Peptides are often shorter and chemically easier to define completely than large biomolecules.

- Proteins also consist of amino acids, but are usually longer and have a stable three-dimensional folding.

- In proteins, functions often only arise through folding, domains and interactions with cofactors.

- Proteins often carry modifications that significantly complicate analysis and comparison between samples.

- Peptides can be folded or cyclic, but do not necessarily achieve the complex architecture of many proteins.

- The boundary between "long peptide" and "small protein" is not technically absolute and is drawn depending on the context.

- What counts for analytics: Sequence, modifications, salt form and purity must be clearly documented.

- What counts for communication: The decisive factor is the intended purpose as a research reagent, not a claimed application in humans.

What types of peptides are there?

Peptides can be categorized in different ways. In research, it is not so much a single classification system that is decisive, but rather the context in which a peptide is used. Length, structure and origin influence how stable a molecule is, how well it can be handled and what it is suitable for in experimental models.

- Short peptides with few amino acids

- Oligopeptides of medium length

- linear peptides without cross-linking

- Cyclic peptides with increased stability

- synthetically produced peptides

- Biologically derived peptide sequences

- Modified peptides with protective groups

- labeled peptides for detection methods

In many laboratories, synthetic variants are deliberately used as they are more reproducible and easier to control than molecules isolated from biological sources. Specific modifications allow properties such as solubility or stability to be adapted without changing the underlying sequence.

Regardless of the classification, the exact description of the type of peptide is a prerequisite for comparable results. Length, structure and modifications should always be documented transparently in order to avoid misinterpretations.

Biological role: what peptides can basically control in the body

Peptides can be categorized in different ways. In research, it is not so much a single classification system that is decisive, but rather the context in which a peptide is used. Length, structure and origin influence how stable a molecule is, how well it can be handled and what it is suitable for in experimental models.

- Signal transmission: Many peptides bind to specific receptors and trigger defined reactions. This makes them ideal for analyzing signaling pathways in isolation.

- Regulation: Peptides can occur as activating or inhibiting factors. Even small changes in concentration are often sufficient to observe measurable effects.

- Structural functions: Some peptides stabilize complexes or influence the spatial organization of larger molecules.

- Interactions: Due to their manageable size, bonds between peptides and target structures can be investigated comparatively precisely.

- Model character: Peptides often serve as simplified models for larger proteins or natural ligands.

- Research relevance: The observed effects originate from controlled experimental systems and are not to be understood as recommendations for use.

It is important to make a clear distinction between biological function and practical use. The roles described refer to natural or experimental contexts and form the basis for scientific questions, not for use on or in the human body.

Why peptides are so frequently used in research

Peptides are regarded as particularly flexible tools in many scientific disciplines. Their defined structure makes it possible to investigate specific questions without having to map the complexity of complete biological systems. They are therefore widely used, particularly in early research phases.

Peptides can be categorized in different ways. In research, it is not so much a single classification system that is decisive, but rather the context in which a peptide is used. Length, structure and origin influence how stable a molecule is, how well it can be handled and what it is suitable for in experimental models.

- Clear and reproducible chemical structure

- Targeted investigation of individual signaling pathways

- High controllability in vitro

- Good comparability between experiments

- Simple adaptation through sequence changes

- Use as reference or control substances

- Suitable for preclinical models

- Compatible with many analytical methods

Compared to complex proteins, peptides can often be synthesized and analysed more quickly. This saves time and reduces variables. For researchers, this means that hypotheses can be tested efficiently before more complex systems are used.

The purpose remains decisive. Peptides are used as research reagents to understand processes and validate models. They are used exclusively in a scientific context and not for human application.

Production and purity:

Where the differences in quality arise in practice

- Synthetic manufacturing processes differ in precision and yield

- Incomplete couplings can generate by-products

- Cleaning steps significantly determine the final cleanliness

- Residual solvents or protective groups influence measurement results

- Batch differences arise due to process fluctuations

- Missing or unclear analytics make comparability difficult

- Salt form and counterions change solubility

- Documentation determines traceability

Stability, storage and handling: what really counts in the laboratory

The stability of peptides is not a fixed value, but depends heavily on the environment and handling. Temperature, humidity and solvents determine how long a peptide retains its chemical integrity. Proper handling is therefore essential for reliable results.

- Temperature: Many peptides are stored refrigerated or frozen to slow down degradation processes.

- Moisture: Hygroscopic properties can lead to rapid degradation. Dry storage is often crucial.

- Light: Certain sequences react sensitively to UV or strong light.

- Solvent: The choice of solvent influences stability and aggregation.

- Aliquoting: Small partial quantities reduce repeated defrosting cycles and material loss.

- Safety: Storage is childproof and in accordance with laboratory standards, regardless of the planned experiment.

Controlled handling not only protects the material, but also the validity of the results. Documented storage conditions and consistent handling are therefore part of the principles of good scientific practice.

Read quality certificates correctly: COA, HPLC, MS and SDS

Quality certificates are key documents for correctly classifying peptides as research reagents. They provide information on identity, purity and safety and make it possible to compare results between laboratories. Without these certificates, it remains unclear what is actually being investigated.

The Certificate of Analysis (COA) summarizes the most important test results of a batch. It contains information on the sequence, the measured purity and often also the analysis method used. A COA should always be batch-specific, as even small process changes can cause differences.

HPLC and mass spectrometry data are used to confirm purity and molecular mass. In addition, the safety data sheet (SDS) provides information on hazards, storage and handling. Only the interaction of these documents allows a well-founded evaluation and responsible use in a research context.

Typical misunderstandings: why "false expectations" arise with peptides

- Equating research data with practical application

- Transfer of in-vitro results to complex systems

- Simplified presentation without context to methodology

- Unclear distinction between scientific observation and value proposition

- Ignoring differences in purity and batches

- Lack of consideration of stability and storage

- Confusion of peptides with authorized medicinal products

- Underestimation of regulatory framework conditions

Research reagent instead of application: Intended use,

Responsibility and secure communication

The classification of peptides as research reagents is not just a formal question, but determines the entire handling of these substances. Intended use means that production, documentation and communication are consistently geared towards scientific use. This clarity protects both users and suppliers.

- Intended use: Peptides are provided exclusively for scientific and laboratory-based research.

- No use: They are not intended for use on or in the human body.

- Communication: descriptions avoid dosages, instructions or usage scenarios outside of research.

- Responsibility: Providers and users bear joint responsibility for proper use.

- Transparency: Analytical evidence and safety information are openly accessible.

- Delimitation: Research reagents are neither medicinal products nor foodstuffs or cosmetics.

Clear and consistent communication prevents misunderstandings and creates trust. It ensures that peptides are understood for what they are: precisely defined tools for investigating biological processes in the context of responsible research.